Section: System dynamics

Finding the right flexibility

Flexibility isn’t a virtue on its own; it only works when it matches the team’s reality.

The moment a system takes shape, a new question emerges: “What kind of flexibility fits the team using it?” The right balance depends on the team’s maturity and the trust that holds it together.

In the previous article, we explored when systems become necessary and how coherence creates leverage. This article looks at what happens next: how systems evolve with the people and culture that use them, and how to assess whether yours needs more stability, more freedom, or a different kind of trust.

Systems as mirrors of maturity

Section titled “Systems as mirrors of maturity”A system reflects the capability of the team that builds and uses it. When skills are uneven or shared understanding is thin, structure helps. Rules bring focus. Guardrails make expectations visible. But the right level of flexibility always depends on context. A small, cohesive team may thrive with minimal guidance, while a larger or less aligned team may need clearer frameworks to stay coherent.

By maturity, I don’t mean tenure or process. I mean the combination of skill, execution, and alignment that allows a team to deliver consistently while adapting to change. Skill is the craft behind the work. Execution is skill in motion, how teams apply that craft to create meaningful work under real conditions of priorities, constraints, and changing context. Consistency is the endurance that keeps quality steady over time. Maturity ties all three together: capability, behavior, and endurance.

The flexibility quadrant. Flexibility grows with trust and shared understanding. Each stage has value. The goal isn’t freedom but fit.

Let’s break it down:

- Large team, low maturity: Rigid. Rules and strong guidance protect consistency when maturity is low or context is still forming. Structure creates safety and focus while teams build shared foundations.

- Small team, still learning: Responsive. Teams begin to stretch within structure. Feedback and iteration help the system adapt without losing its shape.

- Larger team, capable but fragmented: Adaptable. Rules give way to principles. Teams apply judgment, evolve patterns responsibly, and make context-aware decisions.

- Small, experienced team: Flexible. Alignment happens through relationships and intent rather than control. Coherence comes from trust, not enforcement.

The quadrant isn’t a ladder but a reflection of alignment. Different teams in the same company may sit in different places.

When perception breaks alignment

Section titled “When perception breaks alignment”Friction often starts with perception. Every team has a story about who they are and what they’re capable of, but those stories don’t always match reality. Some teams, or individuals within them, overestimate their maturity and resist the structure that would actually help them grow. That bias often appears as a rejection of constraints. When a system reflects what’s really happening, it can feel like criticism instead of clarity. What follows isn’t collaboration but fragmentation: parallel efforts, competing opinions, and an organization that will never reach coherence.

Embrace your constraints.

They are provocative.

They are challenging.

They wake you up.

They make you more creative.

They make you better.

Biz Stone Things a Little Bird Told Me: Confessions of the Creative Mind, 2014

Biz Stone Things a Little Bird Told Me: Confessions of the Creative Mind, 2014 When that misalignment deepens, resistance turns into quiet sabotage. People start optimizing for their own definitions of quality or speed, believing they’re helping while pulling in different directions. Systems work then becomes a negotiation between realities, and the systems team sits in the middle, holding up the mirror.

The goal is to find the level of structure that sustains quality, clarity, and flow as teams grow. Knowing what kind of structure you need is one thing; agreeing on where you really are is another.

Reading the signals together

Section titled “Reading the signals together”The mirror can reveal friction but not fix it. What happens next depends on how leaders respond. Defining where a team sits on this spectrum is a shared responsibility. The systems team usually leads that assessment, but it only works when leadership listens and acts on what the system exposes.

They contribute by bringing clarity through observation, revealing patterns of alignment, capability, and culture. Sometimes clearly, sometimes uncomfortably.

- They see the work up close: Collaboration with designers, engineers, and writers gives them a grounded view of how alignment holds or breaks.

- They translate signals: Patterns in adoption, quality, or decision-making reveal not just capability but culture.

- They keep the mirror clean: Their role is to surface these realities without judgment and make the state of the system visible.

When gaps appear, leaders must decide what to change: priorities, resources, or expectations. When both sides align, flexibility becomes calibration instead of conflict.

The leadership lens

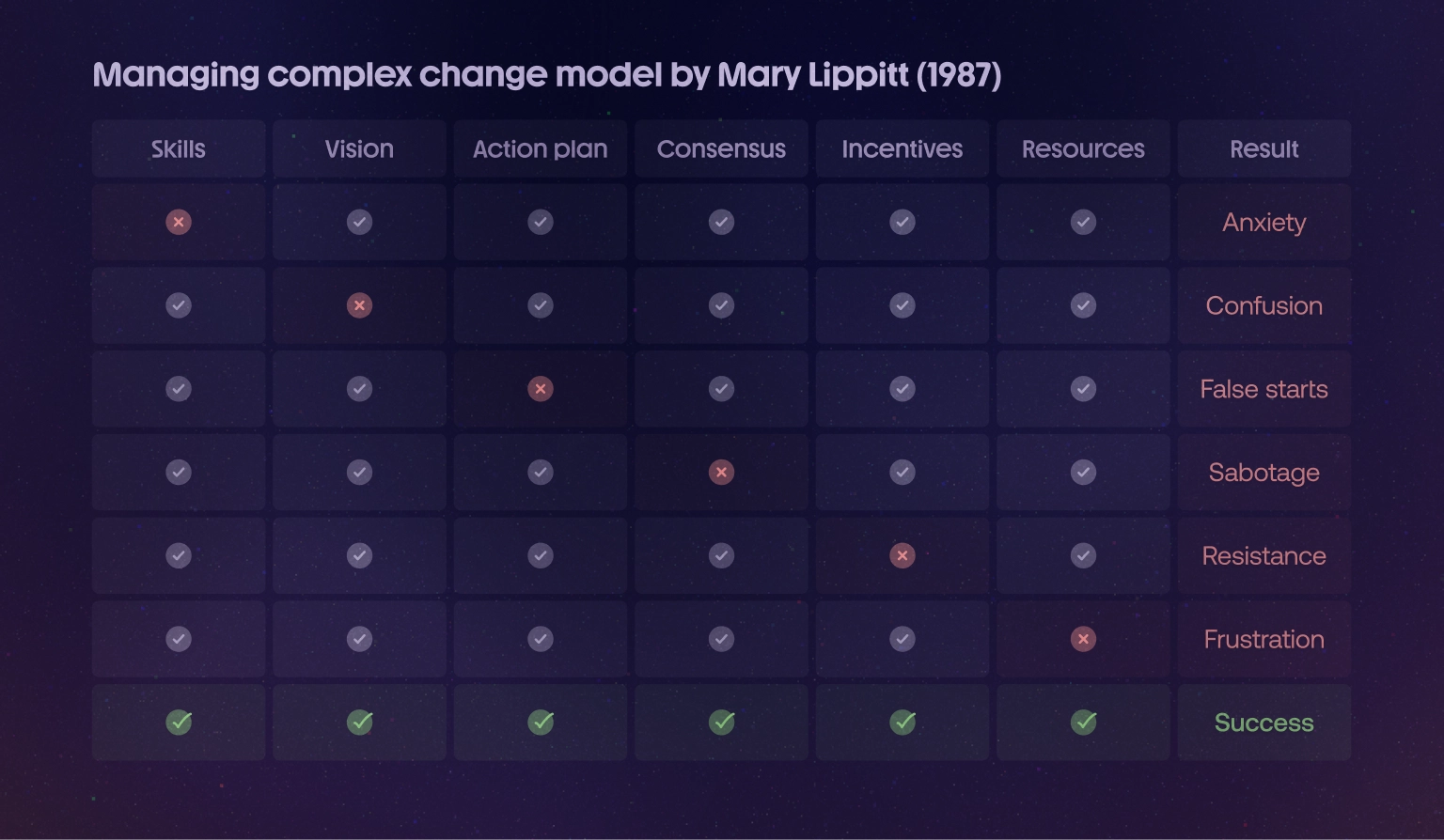

Section titled “The leadership lens”Systems can reveal friction, but only leadership can turn it into progress. Once those signals are visible, the quality of response determines what happens next. As Mary Lippitt’s Managing complex change model shows, change succeeds when vision, skills, incentives, resources, and action move together.

This sequence reinterprets Mary Lippitt’s model through the lens of design systems, where execution bridges craft and collaboration, and shows how alignment turns change into progress.

Functional or craft leadership

Section titled “Functional or craft leadership”Functional leaders connect vision with execution. They translate strategy into practice, set expectations, and keep quality visible in the details. Upward, they create visibility and advocate for resources. Downward, they build teams, nurture trust, and sustain culture through the everyday work of review and iteration.

Organizational leadership

Section titled “Organizational leadership”Organizational leaders define the environment in which teams operate. They decide what work is valued, what gets support, and how success is measured. If executives see systems as documentation or branding, they reduce them to surfaces. That quietly signals that coherence is optional. But when systems are understood as shared infrastructure, they create the conditions for sustainable growth.

Platform engineering has already proved the value of this mindset. By treating shared systems as infrastructure, engineering teams build stability and speed for everyone else to work on top of. The same idea applies to the experience layer. When organizations connect their foundations, components, patterns, operations, and tools, coherence becomes an operational advantage. That’s where systems start to behave like infrastructure rather than libraries. In engineering, platform work can happen quietly. In experience, it happens under a spotlight, where alignment is as emotional as it is operational.

When there’s a gap in maturity or culture, systems stop being neutral. They surface what an organization values, ignores, or resists.

Design systems distill and magnify healthy practices and patterns while exposing and challenging unhealthy ones. The amount of resistance a healthy design systems team experiences is directly related to the unhealthiness of the organization’s established ways of working.

Ben Callahan Founder of Redwoods, The Question, & Sparkbox

Ben Callahan Founder of Redwoods, The Question, & Sparkbox The response to that visibility reveals the gap between what the organization says it values and what it actually rewards. That distance defines culture more clearly than any set of principles or posters ever could.

A popular illustration about innovation and resistance to change, perfect to describe what many systems teams face. Original author unknown. Thanks for sharing, Shaun Bent!

The most effective leaders meet what the system reveals with curiosity, not control. They use visibility to realign priorities, repair trust, and strengthen the foundation that flexibility depends on. But not everyone reacts that way.

- Ignore: The distracted culture. They equate motion with progress, keep building, shipping, and scaling without looking at what the system exposes. In doing so, they preserve inefficiency, duplication, and silent waste that compound over time.

- Reject: The defensive culture. They resist the reflection because it challenges their comfort or control. They question the data, reframe the signal, or dismiss the system as “not representative.” What they’re really rejecting is accountability.

Systems don’t create dysfunction; they make it visible. When leaders ignore or reject that visibility, they trade resilience for comfort. Over time, they weaken the compounding forces that make organizations healthy: quality, delivery, and talent development. Those forces grow slowly but sustain everything else. When they erode, trust disappears first. Without trust, flexibility turns into chaos instead of capability.

Flexibility through trust

Section titled “Flexibility through trust”When leadership acts on what systems reveal, alignment can begin to flow naturally. Rules turn into references, and shared intent guides decisions. The framework remains, but it supports rather than dictates.

Trust grows across disciplines. Designers, engineers, and writers rely on one another’s judgment. Leaders set direction, but teams move with autonomy because they understand both the boundaries and the reasons behind them. Boundaries still exist. They make exploration possible rather than limiting it.

Flexibility becomes cultural. It shows in how people handle disagreement, share credit, and adapt when context changes. Structure still exists, but it’s carried collectively rather than enforced.

Local experimentation sustains that balance. Lightweight spaces such as prototypes, pilot features, or local libraries allow teams to test ideas safely. When those ideas prove valuable, they feed back into the core system. This continuous loop keeps the system relevant without losing coherence.

For teams, that alignment turns systems into decision accelerators and multipliers of collective focus. They reduce friction in daily work, clarify ownership, and let people spend their energy on progress rather than negotiation.

Flexibility, when grounded in trust, makes coherence faster, not tighter. It gives structure room to evolve while keeping intent intact.

Reflection

Section titled “Reflection”Every system tells the truth about the organization behind it. It shows how people understand their craft, how they respond to tension, and how they trust one another to do good work. Structure and culture evolve together, and when one outpaces the other, the system becomes a mirror that makes the gap impossible to ignore.

Each pattern describes a problem which occurs over and over again in our environment, and then describes the core of the solution to that problem, in such a way that you can use this solution a million times over, without ever doing it the same way twice.

Christopher Alexander A Pattern Language, 1977

Christopher Alexander A Pattern Language, 1977 Patterns, like systems, aren’t about repetition but understanding. They help us create coherence without losing individuality, adapting to context while preserving shared intent and creativity.

Rigidity without care breeds frustration. Flexibility without foundation breeds confusion. The healthiest systems move with their teams, grounded in principles, guided by leadership, and sustained by trust.