Section: System dynamics

Experience Platform

When systems stop serving teams and start shaping how they create experiences together, quality becomes culture.

In engineering, platform work often happens quietly. Not only because it’s essential, but because few people understand it. The logic of code is invisible, and the value of infrastructure is assumed. Nobody outside engineering argues about how a compiler should feel.

Experience work is the opposite. It happens in full view of everyone, and everyone feels entitled to an opinion. People have a sense of what looks right, sounds natural, or feels good. Because the work is visible and emotional, people treat it like taste, not discipline.

That’s the paradox. Experience design operates through human senses, but it’s built on structure as deep and rigorous as engineering. Color, language, motion, and tone can look like opinion until you connect them to the systems that define their relationships. Once those foundations are clear and linked, they stop being decoration and become a language that can be taught, governed, and scaled.

That’s what an experience platform does. It exposes the science behind empathy, the repeatable logic that makes perception coherent. It connects the subjective and the objective, bringing every discipline together around one shared language, and turning opinion into a system that can be trusted.

When seen as infrastructure, the conversation shifts from deliverables to capability. Infrastructure is shared, strategic, and continuously supported.

Sam Anderson Director of Design at Intuit

Sam Anderson Director of Design at Intuit From Product Design to owning the experience

Section titled “From Product Design to owning the experience”Every organization reaches a point where intent and structure stop matching. Some teams push for quality while others drift. The gap often shows up first in brand and marketing design: campaigns multiply, timelines tighten, and coherence starts to slip. The work gets faster and louder, but the experience fragments. The problem isn’t talent. It’s incentives. When Brand Design sits under Marketing, brand becomes a service to campaigns, not a function that protects the experience.

When a company decides to split up and separate brand design for everything-else design, it’s usually because of political, inter-personal or efficiency reasons and not because of quality of work. Results in low cohesion & mixed messages.

Rasmus Anderson Founder of Playbit, designer of Inter, Figma, Spotify

Rasmus Anderson Founder of Playbit, designer of Inter, Figma, Spotify At Cabify, this was clear. Brand and Marketing Design were shipping fast but without the time or conditions to build quality. They were buried in campaign work, forced into short cycles with no space for reflection or structure.

Product Design, by contrast, had matured. We worked from principles and systems. The company’s expression no longer felt coherent. The product spoke a more refined language; the brand spoke another.

Why Brand Design doesn’t belong in Marketing

Section titled “Why Brand Design doesn’t belong in Marketing”Marketing optimizes for campaigns, reach, and pace. Those are real responsibilities, but they don’t reward the long view coherence needs.

Branding comes before marketing. It is about who you are, why you exist, what you aim to achieve, and more. Marketing is the practice of expressing your brand to the world.

Bill Kenney Conquer your rebrand

Bill Kenney Conquer your rebrand When Brand Design reports to Marketing, campaign cadence sets the standard. Systems lose care, coherence erodes, and local fixes become the norm. The brand starts chasing attention instead of building meaning. But brand isn’t the end of the chain. It’s the ground beneath it. It belongs to the whole company, as the shared language marketing can amplify.

When ownership flips, brand becomes a deliverable instead of a foundation, and the experience starts to break.

The shift didn’t happen by accident. The vision came from within Design. For years, I pushed the belief, shared and supported by Carlos Tallón, then Head of Product Design, that coherence across brand and product is not a luxury. It’s a responsibility. We proved that vision through the work before the structure caught up. By the time the company was ready to act, the case was already made.

Change didn’t come from a new process or an org chart. It came from doing good work, showing what quality looks like, and earning trust. Over time, the question shifted from “should Design handle this?” to “why isn’t Design already handling this?” That shift is an early sign of maturity. Credibility creates space for integration.

Owning the brand didn’t mean controlling it. It meant being accountable for the entire experience: brand, product, and marketing as one ecosystem. That’s how our Core Design team was born. It brought together Brand Design, the Product Design System, and the (barely existent) Marketing Design System. With those foundations under one roof, each discipline finally had the time and attention to mature and connect. Visuals, language, and behavior began to evolve together. The priority became quality and coherence across the full experience.

The outcomes of this approach

Section titled “The outcomes of this approach”The 2021 brand redesign brought everything together. For the first time, the same foundations supported both product and marketing. We refined what worked and rebuilt what didn’t. The logo, composition, and photography became extensions of the design system, not parallel workstreams.

We finally had a shared language that expressed who we were across every surface. It wasn’t a set of visuals. It was the foundation that let expression scale without losing integrity.

People noticed. Customers could finally see the same care and clarity in every touchpoint. Teams saw their craft reflected in a shared language that matched the quality of their work. It strengthened pride, belonging, and focus. And the company could finally tell one coherent story, built on the same foundation everywhere.

Multi-dimensionality lets the same foundations work across product and marketing without duplication.

Patrycja Rozmus Fractional Design Leader

Patrycja Rozmus Fractional Design Leader Patrycja Rozmus describes this stage as the point where systems evolve across crafts, across people, and across time. You can’t skip those dimensions. You move through them by proving, layer after layer, that coherence saves more energy than chaos.

Beyond design: from coherence to infrastructure

Section titled “Beyond design: from coherence to infrastructure”A design system becomes an experience platform when it stops serving one discipline and starts serving the whole company. It evolves from a toolkit into living infrastructure. This foundation connects human and technical systems so design, content, brand, and engineering can move in rhythm.

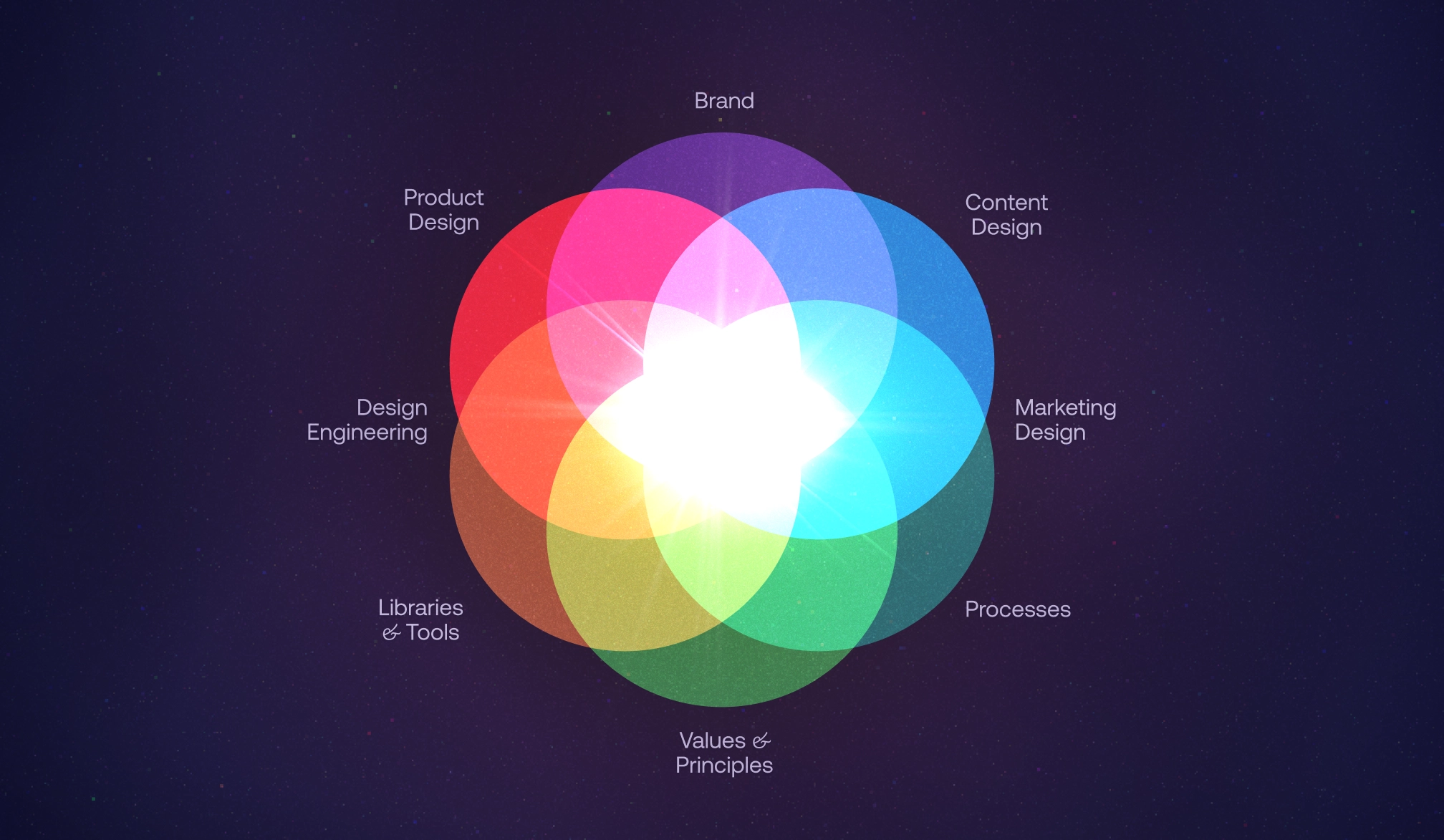

The real magic happens when disciplines work together with a shared purpose: to create a unified experience language. Graphic heavily inspired by Trent Walton.

I didn’t call it an experience platform at the time. We were just trying to build a coherent ecosystem around design. I first heard “infrastructure” used for design systems at GitHub. Their team is called Design Infrastructure, then managed by Diana Mounter. I had always seen design systems as a form of infrastructure, but I didn’t yet know how to explain it. Diana’s framing gave me the words to share that view and describe the work not as decoration but as the structural layer that keeps a company’s experience stable and connected.

Then Jennie S Yip expanded that thinking. In her Figma Schema 2021 talk, she described how Atlassian was rethinking its design system as a platform, something that connects disciplines instead of serving one of them. Listening to her, I realized that what we had built at Cabify followed the same logic. She brought clarity to the link between infrastructure and collaboration. From there I studied how platform engineering succeeds and which principles apply to experience.

The broader shift

Section titled “The broader shift”That talk made me realize the same change was already unfolding in other companies. Atlassian had faced a similar challenge: their design and code documentation had grown apart until the friction became impossible to manage. The solution wasn’t more documentation, it was ownership.

We had to stop thinking of our system as a library and start treating it like a platform that empowers makers.

Jennie S Yip Principal Design Systems Designer at Snowflake

Jennie S Yip Principal Design Systems Designer at Snowflake That mindset let Atlassian’s Brand and Product teams share one system. “We’re no longer the ceiling,” she said later. “We’re the floor.” Once the same foundations supported both, creativity expanded instead of shrinking. Systems stopped being limits and became enablers.

When disciplines align, a few things always happen:

- The story feels coherent: From the first impression to the last screen, everything speaks with one tone and one logic.

- Quality compounds: Improvements in one area raise the bar for the rest.

- Teams learn faster: Makers challenge assumptions and grow together.

- Systems gain reach: Shared foundations cut duplication and make new expressions easier to build.

Pinterest’s Gestalt shows this with continuous releases and automatic documentation, maintained together by designers and engineers. Brainly’s Pencil went further with tools that translate design tokens into production code. Both behave like infrastructure, not projects.

Once systems connect all disciplines, they stop being a tool for designers and become a shared foundation for the entire organization. Coherence stops being a goal and becomes the way the company works.

From Design to Experience Design New

Section titled “From Design to Experience Design ”NewOne of the quiet challenges in this work is language. When we say “Design,” many people still hear visual design. Screens. UI. Aesthetic decisions made late in the process.

But that’s not the work we’re talking about here.

At Maze, Roger Bretos renamed the Design team to Experience Design. The change wasn’t cosmetic. It was a way to make the responsibility explicit: the team wasn’t there to design interfaces, but to shape how people experience the product end to end. That included product design, user research, content design, and the connective tissue between them. It also created a more natural bridge to brand and other disciplines that influence experience beyond the product UI.

This shift matters because names set expectations. Calling the function “Experience Design” makes it harder to reduce the work to visuals or execution. It signals that the team owns the quality of the experience, not just how it looks. It also gives the organization a clearer place to anchor cross-disciplinary work that doesn’t fit neatly into Product, Marketing, or Engineering.

In my experience, this kind of clarity is often a prerequisite for experience platform work to exist at all. If the function is framed too narrowly, the platform will be treated as a design system or a set of components. When the function is framed around experience, the platform can grow into something broader: a shared language, a set of standards, and a way of working that connects teams instead of fragmenting them.

Roger’s write-up goes deeper into how this shift played out in practice, from team composition to operating model. It’s a useful reference for anyone trying to give experience work the space and legitimacy it needs to scale.

Why Experience Design is the right organization to support this platform

Section titled “Why Experience Design is the right organization to support this platform”An experience platform only works if the organization can sustain it. You can build the best system in the world, but if ownership is fragmented, it breaks into local versions and workarounds.

What holds it together is not hierarchy but shared purpose. Companies need a place where all disciplines meet as equals, and a function that cares about coherence as much as delivery. In most companies I’ve worked with, that place didn’t exist until Design created it. In the few where Engineering tried to hold that role, the focus naturally shifted toward technical outcomes. Experience never was the primary goal.

My take on the Priority of Constituencies principle by the W3C, later adapted to design systems by Jason Grigsby and reflected by Luke Murphy. It’s a bit shorter, and more focused on broader platform work.

Engineering, Product, and Marketing have critical responsibilities. But Engineering has many other priorities to balance, which makes it harder for experience to stay central. And Marketing is optimized for campaigns, timelines, and specific audience goals, which quite often leads to resistance when asked to invest in shared foundations or long-term coherence. Holding a wide, sustained view of the experience is rarely possible there, even when teams try.

Experience Design is the only team whose main concern is the experience itself. That focus keeps the platform grounded in people, not process.

Experience Design is not a layer above others. It connects them. It’s responsible for how the company feels, not just how it looks. It translates between the languages of Brand, Product, Marketing, Content, and Engineering so intent survives implementation.

The next sections look at how this connection works in practice, through Design Engineering and through Content Design. These are two of the most powerful and often misunderstood dimensions of the platform, the parts that turn principles into real experiences.

Why Design Engineering finds a home inside Experience Design

Section titled “Why Design Engineering finds a home inside Experience Design”Companies call these roles many things: UX Engineer, Design Technologist, Frontend Designer. Titles change, but the work stays consistent: bridging design and code, and turning intent into behavior.

As Diana Mounter explains in Design Engineering: The next era of Software Design, Design Engineering takes many forms. Some focus on expressive brand and marketing work, others on system foundations or product polish. What unites them is fluency in both design and implementation.

Frontend has become so broad that the layer users actually feel, HTML and CSS, often gets deprioritized.

Diana Mounter VP of Design at AlphaSense

Diana Mounter VP of Design at AlphaSense That layer is where an experience platform lives: semantics, layout, motion, and behavior. When it gets pushed to the edges of frontend practice, someone has to protect it on purpose. That’s why ownership matters. Experience Design treats HTML, CSS, and accessibility as experience decisions, not delivery details.

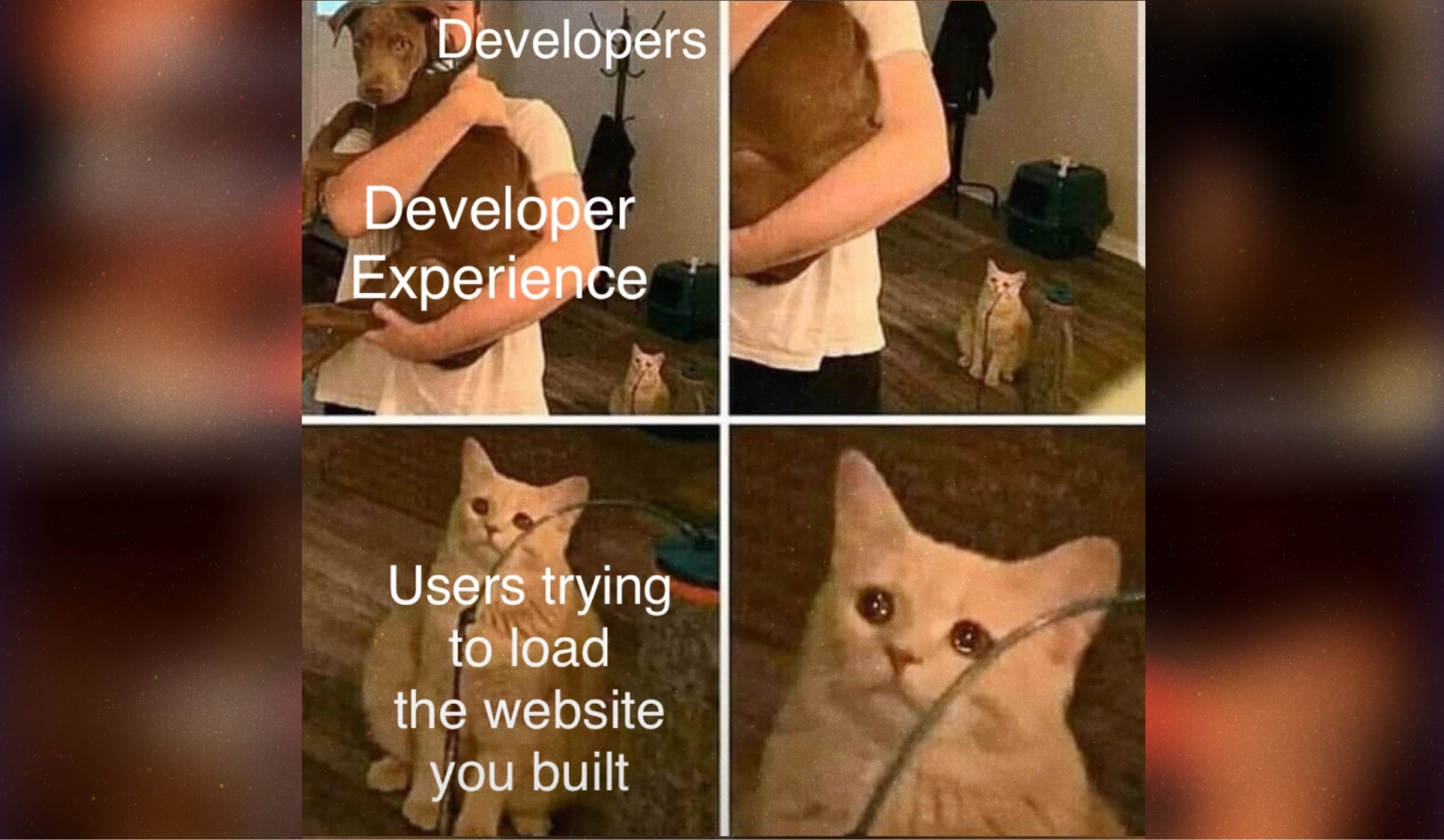

Developer Experience and Design Engineering share tools and methods, but they optimize for different things. Developer Experience optimizes for developer workflows. Design Engineering optimizes for what people feel when the work ships. That’s the clearest line between platform engineering and the experience platform.

Andy Bell jokes that some developers are hugging DevEx while their users wait for the page they made to load. It’s a light comment, but it captures the difference clearly. Developer Experience makes it easier to build. Design Engineering makes what is built feel right.

Supporting hybrid roles

Section titled “Supporting hybrid roles”Design Engineers often struggle to find a home. Inside Engineering, attention drifts to frameworks, performance, and internal tooling. Peers may not understand why they care so much about interaction details and accessibility. Inside Design, peers may not understand their code or the constraints they are working with.

What they need is a space that respects both sides, and a management layer that can support them. Without that space, these people plateau. They end up translating between teams instead of leading the experience work they are best positioned to shape.

Experience Design has to mature to support them. Create career paths for Design Engineers. Offer mentorship from hybrid leaders. Give them space to grow from implementer to architect. Keep them close to Engineering so they stay technical, and anchored in Design so they stay human.

I saw the cost of missing support at Cabify. Our system was working well, but there was no dedicated design systems leadership. Fran, our Design Engineer, had a manager whose focus lived in another team. He had no clear path and no sponsor to help him grow inside this hybrid space. Even if nobody said it aloud, the message was that the system could run on its own. The work stayed strong, but the role stopped evolving, and in the end that lack of support pushed him to leave. As someone who had spent years working across design and frontend, I could see how easily these roles fall between disciplines when the work has no one to represent it. That realisation stayed with me.

I don’t associate with being a Software Engineer. I associate with being a UX Engineer. However, because UX Engineering doesn’t have the career support that Software Engineering does; I need to masquerade as something I’m not just to succeed in a field and have a possibility of promotion.

Donnie D’Amato Principal UX Platform at GoDaddy

Donnie D’Amato Principal UX Platform at GoDaddy These gaps aren’t rare. They show up in many teams, even when the work is strong. What matters is what we choose to do about them.

At Maze, I finally had the chance to act on them. I joined the company as a Design Infrastucture Manager because the work needed someone who could support it across teams, not only inside the craft. The Director of Platform Engineering and I partnered to move Philip, our Design Engineer, from Developer Experience into Design Infrastructure. That decision wasn’t about territory. It was about giving him the sponsorship and structure hybrid roles need, backed by the conversations that shape how teams work together. The lesson from Cabify guided that choice: systems grow when someone is looking after the work and the people behind it. That understanding reshaped how I approached management. I wanted everyone on the team to have the support, clarity, and direction that had been missing before.

When Experience Design owns the experience platform, Design Engineering becomes a first-class function. These engineers move from supporting design to shaping it. They build the architecture of interaction: semantic HTML, scalable CSS, accessible components, and clear APIs that carry experience logic into production. They protect the very layer Diana describes as deprioritized and treat it as the core of the experience, not a delivery detail. They stop being an edge case and become what they were always meant to be: the technical backbone of the experience.

Why Content Design is the missing part of the puzzle

Section titled “Why Content Design is the missing part of the puzzle”If design defines how something works, content defines how it makes sense. Content Design turns complexity into understanding. It guides, reassures, and connects people with products.

Too often, writers sit alone, serving everyone but belonging nowhere. Their work is split across Product, Marketing, and Support, without a shared structure to keep the company’s voice coherent.

If we want a real experience platform, Content must sit beside Design and Engineering, not downstream from them. Language needs the same rigor as tokens and component specs.

Language is an absolutely crucial, and often extremely overlooked, part of the success of a design system.

Jess Sattell Principal Content Designer, Spectrum Design System at Adobe

Jess Sattell Principal Content Designer, Spectrum Design System at Adobe At Maze, I could finally put this into practice. Ola Kosicka, our UX Writer, worked with our designer and engineer from the start. Her analytical, systematic approach fit the team’s way of thinking. Together we created shared principles for clarity, consistency, and tone, and embedded them into the system.

The impact was immediate. We worked as one group instead of passing files between silos. Quality and morale went up. Reviews expanded beyond spacing, code, and layout to include phrasing, behaviors, hierarchy, and empathy. We learned so much from each other.

What content brings to a platform mindset:

- Coherence through language: voice, tone, and terminology become foundations, not afterthoughts.

- Design that speaks: components and patterns documented with real, intentional language work better in context.

- Shared understanding: when content is part of the system, everyone designs with clearer intent and fewer assumptions.

- Inclusion through clarity: plain language is accessibility. It welcomes more people into the experience.

Including Content Design completes the circle. It makes the foundations human, not just functional. Without Content Design, systems feel mechanical. With it, they speak with empathy and intent.

Why (probably) you don’t need a Product Manager

Section titled “Why (probably) you don’t need a Product Manager”When a Product Manager adds value, it’s usually by creating clarity across many moving parts: portfolio planning at scale, coordinating budgets and vendors, or helping leaders navigate trade-offs. Those responsibilities are real, but they aren’t what shape the experience. Mature teams can set direction together without a dedicated Product Manager.

Traditional product management optimizes for output, delivery speed, and measurable short-term progress. Platform teams optimize for something slower but deeper: long-term quality, maintainability, and coherence. Those results don’t fit sprint pacing.

Products ramp up and ramp down. Infrastructure endures.

Sam Anderson Director of Design at Intuit

Sam Anderson Director of Design at Intuit That endurance is the point. Platform work doesn’t behave like product work. It isn’t a feature roadmap but shared infrastructure, built with standards, expectations for reliability and support, and clear adoption plans. In most cases, a strong triad of Design, Engineering, and Content leads can set direction, prioritize, and coordinate with the teams who depend on them. Platform work is care made repeatable.

What makes this model work:

- Clarity of responsibility: define who owns which decisions and how others can contribute. Transparency prevents duplication and confusion when priorities overlap.

- Quality in production: track quality and adoption together as your north star, the best measure of whether the system works as intended. More on this soon.

- Open and predictable roadmap: keep a public roadmap that shows what’s coming next and when. Predictability helps other teams plan with confidence. Thanks for all the lessons you shared with me, Harvey.

- Balanced responsiveness: allow other teams to influence the roadmap, but keep focus on long-term coherence. Step in to support high-impact initiatives without turning the roadmap into a service queue.

- Shared success: collaborate with Product and Marketing as peers in coherence. Align priorities, share accountability, and keep open feedback channels instead of treating them as customers.

A platform team’s best Product Manager is its own shared sense of responsibility: to quality, to the people who build on its work, and to the standards that sustain the organization.

Experience platform principles New

Section titled “Experience platform principles ”NewExperience platforms sit between disciplines, teams, and evolving needs. Without clear principles, this work can drift into reaction mode, local optimization, or system purity that no longer serves the experience. The principles below differ slightly from platform engineering’s, focusing instead on keeping experience work grounded as organizations scale.

Governing principle: Audience over makers over shapers over theoretical purity. Experience platforms exist to serve real people. When trade-offs arise, audience needs come first. The needs of the teams building the experience, the makers, come next. The needs of the people shaping and stewarding the platform exist to support both, not to outrank them. Theoretical purity comes last. When rules protect one layer but harm the experience, they must change.

- Shape the experience together. An experience platform must be shaped by a multidisciplinary group of equals. Design, content, engineering, brand, and related roles each hold part of the experience, and no single discipline can define it alone. Shared authorship leads to better judgment and stronger care, but it also requires clear ownership and sponsorship to protect that space. Without it, the platform fragments or becomes dominated by a single perspective.

- Serve with intent, not by default. Experience platforms support many teams, and service is part of the work. But serving everything equally turns a platform into a queue instead of a foundation. Requests are understood in context and acted on based on impact, timing, and scale. Sometimes the right response is to help directly. Sometimes it’s to delay, redirect, or invest in a broader improvement that removes the problem altogether. Service here is deliberate. It’s guided by judgment, not volume.

- Protect coherence as the language evolves. Experience platforms support different expressions across product, communication, and brand. Within each context, makers need room to adapt, experiment, and respond to real constraints. Local components and one-off solutions are expected when they follow the shared experience language, and that language itself should evolve through intentional use at the edges. Problems arise when change becomes accidental or silent. Breaking foundations, behavior, or semantics “just this once” increases cognitive load and erodes trust over time. This principle keeps coherence and progress moving together.

Reflection

Section titled “Reflection”This is a lot. Building an experience platform asks more of teams than most work does. It requires patience, long-term thinking, and the willingness to care about things that aren’t always visible or rewarded right away. It’s exhausting.

And still, I believe it’s worth fighting for.

I often describe this stance as idealistic pragmatism. You need a clear vision of what a great experience could be, and the pragmatism to work within the constraints that make it hard to achieve. Without the idealism, the work collapses into maintenance. Without the pragmatism, it never survives contact with reality.

Sometimes you can’t change the broader organization… But you can get close to the critical initiatives and show how the design system provides value there.

Sam Anderson Director of Design at Intuit

Sam Anderson Director of Design at Intuit Not every company needs a large platform function or a formal structure around it, and that’s ok. And when the need for more structure does appear, the work takes time. It asks for trust, patience, and the willingness to carry a point of view long before the organization is ready to support it. At Cabify, it took years of proving value before the company was ready to act. At Maze, we brought Design Engineering, Content Design, and Product Design together, but other parts of the puzzle stayed out of reach.

That’s the reality of this work. You can take it far, but some decisions sit above you, shaped by incentives, timing, and organizational maturity.

That’s why this work asks for resilience. You may not see the finish line. You may do everything right and still fall short of the ideal state. But the effort is never wasted. It plants seeds. It raises the standard. It shows what’s possible.

And when leadership does decide to back that work, those seeds grow into something real: a platform that lets teams build with clarity, care, and pride.